Addiction : adverse childhood experience,

Homeopathy, and neuroplasticity

What is

addiction?

Addiction can be defined as any behaviour that

is associated with craving and temporary relief, and with long-term negative

consequences, that a person is not able to give up despite their best

intentions. Addiction is normally associated with drug abuse, but the

definition can extend much wider than that. One can be addicted to shopping,

food, sex, gambling, work etc.

Although some addictions are definitely more

damaging than others, neurologically there is only one addiction process no

matter what the behaviour or substance a person is addicted to. All addictions

engage the same neural pathways, the same brain chemistry, and the same reward

system.

Why is it that the addict will continue to

persist in their addiction at the expense of their careers, family, finances,

psychological integrity, physical health, and even their life? How can a

substance or harmful behaviour have such a binding hold on a person?

A common belief is that addiction is a choice

that people make – a choice that they make freely, and a bad choice. Therefore

it is appropriate to punish drug addicts with extreme legal sanctions.

The modern medical approach to addiction is that

it is a brain disease caused by genetics that then impairs brain function. This

has some truth. However if it is just a bad choice then why call it a brain

disease, and if it is a brain disease caused by genetics then why punish

people? This does not make any sense.

Even if you are born with genes that supposedly

pre-dispose you to addiction, it is the environment which dictates whether or

not you will succumb or not – whether these genes become switched on or remain

off (epigenetics).

What the ‘choice’ and ‘genetics’ viewpoints have

in common is that they both take society off the hook. If we accept these

definitions then we don’t have to look at the deeper reasons for addiction.

These deeper reasons for addiction actually have very little to do with personal

choice or genetics, and are much more associated with early adverse childhood

experiences, stressed and overwhelmed parents, and a fragmented and unhappy

society.

Yet another view of addiction is that the

substances that are abused are in themselves addictive. But if that were true

then everyone who had a drink would be in danger of becoming an alcoholic. The

fact is that the majority of people can try even very strong drugs like crystal

meth or heroine and not become addicted to these substances. The question

should be why do some people become

addicts where others do not?

Adverse Childhood

Experiences:

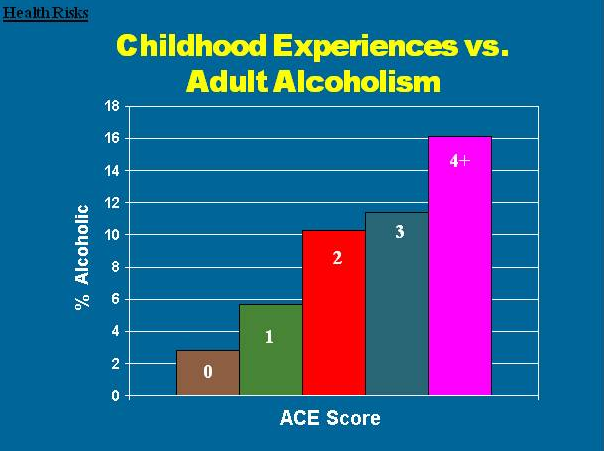

There is now heaps of research studies showing

conclusive links between adverse childhood experiences (ACE’s) and addictive

behaviour. The major piece of research involved over 17,000 people and

indicated an overwhelming correlation between adverse childhood experiences and

addiction later in life. The higher one’s ACE score (i.e. one has

suffered more adverse childhood experiences) the more likely it is for one to

develop addictive behaviour later in life. In fact for each ACE a person’s

likelihood of addiction increases by about 200%.

The graph above shows how the likelihood of

being an alcoholic as an adult exponentially increases with having suffered

adverse childhood experiences. ACE’s are things like emotional or physical

abuse/neglect, sexual abuse, witnessing family violence, absent parent/no

parents…

Not everyone who is traumatised becomes an

addict but early trauma is proven to radically increase likelihood of

addiction.

Gabor Mate, a Canadian doctor who works in

Vancouver’s impoverished drug area, says that out of the thousands of female

drug users he has seen, every single one of them had been sexually abused as a

child. That is quite a revealing statistic. The fact is that almost all addicts

are really just damaged children trying to self-medicate.

Any addictive behaviour is actually an attempt

to self-medicate. Drug addicts will say, ‘the first time I took heroine it was

like being wrapped up in a warm soft hug’, ‘when I took cocaine it made me feel

normal for the first time in my life’. Addicts say that a drug takes away their

pain, soothes, gives a sense of control, makes them feel able to function,

de-stresses them… etc.

So maybe the real question should not be ‘why

the addiction?’, but ‘Why the pain?’

Building a brain:

So we know for sure that there is a strong link

between what happens (or doesn’t happen) in early childhood and addiction. But

why is this?

The key thing to really understand here is that

the human brain actually develops though interaction with the environment. This

is no longer theory – we know it for certain.

According to the research, the key factor that determines the

development of the infant brain is the relationship and connection with those

around esp. the primary care giver(s) – usually the mother. People

connection=neural connection.

In other words the neural pathways of the brain are set

early on by the mutual responsiveness of parent-child relationships. The more

present and responsive the care-giver is to the infant, the more neural connections

are made in that infant’s brain. The type

of attention will determine the type

of connections that grow.

In an infant’s life there are periods when every second millions of connections are being made. The human

brain is the only one that continues to grow outside the uterus at the same

rate as it does inside the womb. We are actually born premature compared to

other animals (i.e. compared to a horse that can run on the first day). This

means that most that most of our brain development happens after we are born. The

human brain is 80% mature within 3 years of life.

So the brain develops through this interaction with the environment in

first three years of life. The circuits that get stimulated will grow and the

ones that do not will atrophy or die.

As an extreme example, if a child is left in the dark the visual

circuitry will not develop and that child will be blind – forever – because the

visual circuitry needs to be stimulated by light in order to grow. Imagine In

an infant whose mother is suffering from post-natal depression. The mother will

lack a feeling of connection to her child, will be less available and less able

to sooth the child, will be less responsive to that child, and may even neglect

its basic needs (in severe cases). This will influence the infant’s developing

brain and which circuits develop or atrophy. This hard-wiring of the brain

occurs very early on in life and sets the patterns for behaviour, and stress

handling ability later in life.

In double blind experiments on mothers with post-natal depression with a

control group of non-depressed mothers they could tell by looking at the EEG of

the infants whose mothers were

depressed and whose was not depressed.

The neuro-chemicals of addiction:

The three main neuro-chemical circuits involved in addiction are

endorphins, dopamine, and cortisol. Understanding how these three circuits are

‘built’ during infancy through interaction with the environment, in particular

the primary care-giver, and how they operate, is the key to understanding

addiction in all its forms.

Endorphins and love:

One main class of drugs are the opiates (from

the opium poppy). These include morphine, codeine, and heroin. The opiate drugs

are extremely powerful pain relievers. Opiates sooth both physical and

emotional pain. Brain scans show that physical pain and emotional pain are felt

in the same area of the brain. When someone is hooked up to an EEG and

experiences physical pain or emotional pain, the same areas of their brains

light up. How is it that these chemicals derived from a poppy even work in our

brains? It is because our brains have receptors for opiates. Why do we have

receptors for opiates? We actually have receptors for our own endogenous

opiate-like substances called endorphins. One of the functions of endorphins is

to relieve pain. Imagine how life would be if we had no mechanism in place with

which to relieve pain?

Endorphins are also the neurochemical of

pleasure. People who have very low endorphin levels may feel depressed and take

no joy in life. Exercise releases endorphins which accounts for the high

experienced by long-distance runners. Imagine life without the ability to feel

pleasure?

Most importantly, endorphins are released during

the loving interaction of people, especially between mother and child. In

experiments with rats and monkeys, if endorphin receptors are blocked, the

mother will not bond with or take any interest in her offspring, and the

offspring will not thrive. In this way we can see that without endorphins life

would not be possible.

In infants whose mothers are not present,

loving, and connected, the endorphins will not be flowing and so this endorphin

fed pleasure/pain/bonding brain circuitry does not properly develop. One can

understand how this might leave the person more susceptible to addiction later

in life, as they will become dependent on getting the endorphin substitute they

need from an outside source.

Dopamine and

reward:

Dopamine is another important neurotransmitter

involved in the addiction process. Dopamine is the incentive or motivation

hormone and flows when you are seeking food or a sexual partner. It is the

brain chemical implicated in curiosity, interest, novelty, feelings of

alertness and aliveness. If your dopamine receptors are knocked out you take no

interest in anything - a zombie-like state. You won’t even feed yourself. The

more dopamine in your system, the more alive, engaged, and motivated you will

feel.

The more exciting something is perceived as

being, the more dopamine is released. The addict’s dopamine response is very

linked in to their addiction, meaning that even thinking about their addiction

will trigger dopamine which then drives them on to seeking out their substance

or behaviour even if another (wiser) part of themselves knows it is not a good

idea. This is why addicts have extremely poor impulse control and find it very

difficult to stop their addiction even though they may want to. If it were a

matter of ‘just saying no’ then there would not be so many addicted people!

All the stimulant drugs (amphetamines, cocaine,

coffee, tobacco) increase dopamine levels. A shot of cocaine increases dopamine

by 300% meth-amphetamine by 1200%.

The other thing that increases dopamine levels

is any risk taking activity; extreme sports, gambling, illicit or novel sex.

The greater the risk, the greater the dopamine kick. The problem is that the

addict’s dopamine circuits get wired to the addiction, whatever form it takes.

So, for the shopaholic, their dopamine circuit gets wired to their shopping

addiction. The addict will often say that their addiction is what makes them

feel most alive, most engaged, most motivated. When the addict is not engaged

in their addiction, their dopamine level is low and they feel withdrawn,

dis-interested, anxious etc. This begs

the question, is it the drug/behaviour that people get addicted to, or is it

their own dopamine?

Cortisol and

stress:

Cortisol is a stress hormone. It helps to maintain fluid balance, blood

pressure, blood sugar and a host of other things when we are experiencing undue

stress. It is similar to adrenalin although has a longer lasting action.

Adrenalin’s affect is more immediate and passes more quickly compared to

cortisol. Cortisol levels rise dramatically in the face of stress as a useful

and necessary response to deal with the immediate threat. Stress raises

cortisol levels which enable us to more effectively deal with a challenging or

dangerous situation by increasing our heart rate, blood oxygenation, glucose

levels, and a host of other things.

Experiences during infancy are known to affect the organism’s ability to

regulate cortisol levels. While stressful early experiences have been

associated with deregulated cortisol levels, positive early experiences, i.e.

high maternal caregiving quality, contribute to more optimal cortisol

regulation (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23116166) . The

infant’s stress regulation response is undeveloped and is mediated by the

mother through soothing contact and attuned responsiveness. So, a well-bonded infant with a responsive

attuned mother will mean that the infant will develop healthy stress regulation

circuitry. However, an absent, tuned out, stressed out, or depressed mother

will mean that the infant will not develop healthy stress handing ability, and

so will remain chronically stressed with raised cortisol levels.

There is a clear link between a person’s ability to handle stress and the

likelihood of developing addictive behaviour. Addiction is about

self-soothing. Due to the stress

regulation patterns set up in early infancy, adult addicts not have learned how

to regulate their own stress response and so will experience more stress, and

longer lasting stress from a lesser stimulus. One can then understand that they

are more likely to fall into addictive patterns of self-soothing with drugs or

other forms of addictive behaviour.

As an aside, chronically raised cortisol levels are related to a whole

host of health problems including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and

osteoporosis. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1993964/

These three circuits - for the opiate love chemistry, for the dopamine

reward system, and for cortisol stress regulation, are all set up during early

infancy mainly through mutual responsiveness between the infant and the mother.

If there is any major or ongoing disturbance or trauma in the infant’s early

environment, this will shape how these circuits function as the person goes

through life, and therefore how prone this person will be to self-soothing

addictive behaviour.

For the healthy development of the infant’s brain neural chemistry it

requires that the care-giver is not stressed, is present, relaxed, consistently

available and attuned to the infant.

This is not about blaming parents though.

Most parents are loving, attentive, and want the best for their children. Most

parents would never knowingly do things that will impact their child’s

well-being. However, it is not just about things that shouldn’t happen

happening, but about things that should happen not happening. D.W. Winnicott

[the late British child psychiatrist] said that there are two things that can

go wrong in childhood: things that happen that shouldn’t happen — that’s trauma

— and things that should happen that don’t happen. Children are equally hurt by

things that should happen and don’t as they are by things that shouldn’t happen

but do. If the parents aren’t emotionally available, [for example], no one will

define that as trauma, but it will be for the child. If a mother has post natal

depression, that’s not defined as trauma but it is likely to lead to emotional

neglect, consequently interfering with child brain development.

Of course it is impossible for a parent to be emotionally available and

non-stressed all of the time. For one thing, we live in a highly stressed

society. Often both parents have to work in jobs that they don’t like just in order

to pay the bills. Or the young mother is herself traumatised, isolated,

stressed, and has no support. Also, the nuclear family is not necessarily the

ideal model for healthy non-stressed child rearing. So the African proverb

states: ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. Now days most parents do not even

have extended family living nearby to help with raising the children. The

current way that we live so separate from each other is only a very recent

phenomenon (probably due to economic growth). The fact is that humans have

lived in small communities for tens of thousands of years, and it is only

relatively recently that we have moved to the nuclear family model.

So, in this context, addiction is a disease of our culture, and not of

the individual. It is our society that is sick, and this expresses itself in

the individual in a myriad of ways, one way being addiction. What if it is what

happens in peoples’ lives that makes them addicted? Then we have to look at our

society, the way we treat each-other, the way we bring up our children, the

mechanisation of childbirth, the split from nature and the wanton destruction

of the environment for the sake of economic growth.

As an example consider the first nations aboriginal people. Aboriginal

people used substances like peyote, alcohol, tobacco, psychotropic mushrooms

without any problems with addiction. These substances were always used in the

context of a sacred ceremony for the village. It was only much later after

these cultures had been violently crushed, raped, dispossessed of their lands,

their freedom, and their right to practice their religion that they developed

addiction problems. The current accepted ‘truth’ is that aboriginal people have

a genetic predisposition towards alcoholism and that’s why they became

addicted. Yet if it were just down to the genes then they would have been

alcoholics a long time ago because genes do not change in a population within a

few decades.

The road to recovery

So, if the tendency towards addictive behaviour is hard-wired into the

infant’s brain through painful early experiences, is there any hope of recovery

for the adult addict? The answer is a resounding ‘yes’. Fortunately the brain

is ‘plastic’,

meaning that it has the ability to re-wire itself and make new neural pathways,

and so the addict is able to change their behaviour. This can take a long time

though and certainly does not happen over-night. The little story below gives

an idea of how the brain builds new neural pathways:

As sheets of snow fell, two high

school buddies and I had a daring idea.

Hanging in the barn was the rusty

hood of a Volkswagen Beetle, and our thoughts went downhill from there,

literally. Its rounded shape, narrow in the front and wide in the back, made

the car hood the perfect giant sled. And the most dangerous slope we could

think of was a straight shot down an old logging road that descended what we

simply called “the mountain.” On the left side of this steep and rutted gravel

road a hill rose dramatically, but to the right a bank fell sharply to a wooded

valley.

Fresh, unpacked snow can make for

slow sledding. So to get the trail started we got a running start at the crest

and then all three of us recklessly leaped onto the curved hood. It bored down

the road, but soon careened over the right edge toward the valley where we

smashed into a tree. Bruised, aching, and laughing about it, we then devised a

plan to correct the failed track. We dragged the hood to the place where we

veered off the logging road, and then walked the hood the rest of the way down

the hill. By doing so, we created a groove in the fresh, deep snow, so that the

next time we rode down the hill we could avoid the original path that led to

the uncomfortable crash. At the top of the hill again, less reckless and more

intentional, we got another running start. The makeshift sled shot down the

road, and when we reached the exit to where we had crashed we leaned to the

left to stay on track. We flew past the danger point and gained such momentum

that the hood propelled the three of us across a creek at the bottom of the hill.

The new pathway that we took time to build had been the key to our success.

To break an addiction it is not enough to just stop or suppress the

addictive behaviour, but one needs to replace it with something new (and

healthy!). One needs to intentionally create a new brain patterning by changing

one’s thinking and behaviour to more healthy life-affirming pursuits.

Healing the original pain - How homeopathy can help people with addiction:

Consciously rewiring the brain by changing one’s behaviour will help with

addiction, but the addict will need to dig deeper if they are truly to overcome

their addictive nature. Because the susceptibility towards addiction begins

with traumatic brain-wiring experiences that occur early in childhood, it is

through healing of these past experiences that the foundation for addictive

behaviour is dissolved.

Homeopathic treatment can help a great deal with this, as it gives

self-insight into the nature and origins of one’s addictive patterning and has

the power to heal at a very deep level.

Healing is not about just fixing the symptoms, or, in the case of addiction, rewiring the brain. Healing is about treating the whole person; understanding the dis-ease within the context of the person's life history, taking into account all aspects of their nature, inherited predisposition and susceptibility. This approach fits perfectly within the remit of homeopathy in which every aspect of the individual is considered - physical, psycho/emotional, spiritual.

The homeopathic approach always views addiction (or any illness) as an expression of dis-harmony within the whole person. It recognizes that all symptoms are part of the whole and nothing stands in isolation; the person's neural wiring is not a separate entity in its own right. This of course is an absurd idea, but it does tend to be the view that conventional medicine takes regarding disease. This is why there is a different specialist for every part of your body, and they often don't talk to each other!

Healing is not about just fixing the symptoms, or, in the case of addiction, rewiring the brain. Healing is about treating the whole person; understanding the dis-ease within the context of the person's life history, taking into account all aspects of their nature, inherited predisposition and susceptibility. This approach fits perfectly within the remit of homeopathy in which every aspect of the individual is considered - physical, psycho/emotional, spiritual.

The homeopathic approach always views addiction (or any illness) as an expression of dis-harmony within the whole person. It recognizes that all symptoms are part of the whole and nothing stands in isolation; the person's neural wiring is not a separate entity in its own right. This of course is an absurd idea, but it does tend to be the view that conventional medicine takes regarding disease. This is why there is a different specialist for every part of your body, and they often don't talk to each other!

The addict can be viewed as being ‘stuck’ at a particular stage in their

life when the painful experiences occurred. Basically, something happened to

them (usually at a very young age), and they have never recovered. This is why

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and addiction are so intertwined. The

neural pathways (and therefore behaviour patterns) are set in response to these

early experiences, and so the person becomes stuck at this place in time,

behaving and responding in the present time as if these painful experiences

were still occurring. This phenomenon is known as implicit memory.

True health is not only about being free from physical pain and

suffering. In true health we are also free from our past pain and conditioning

so that we can respond appropriately to the present circumstances whatever they

may be. The key word here is ‘appropriately’. As an example, a baby who

experiences maternal abandonment will, as an adult, tend to re-experience or

interpret abandonment even when this is not actually happening. They will be so

keyed into this brain groove that they will interpret and perceive abandonment

in situations where they are not actually being abandoned. Also, if this person

experiences (or perceives) abandonment as an adult (and we all do at some point

in our lives) they will re-experience very intensely all the associated

feelings they experienced as an abandoned infant – terror, anxiety,

worthlessness…

In this way we can see how dis-ease is an inappropriate response – a

stuck ingrained pattern that has its roots in our early conditioning.

True health does not mean that we are pain free, but that the pain is in

proportion to the current situation. For example your partner criticizes you

for not doing the washing up properly, and you experience crushing rejection,

humiliation, and rage... This is an out of proportion reaction and we need to

realize that this reaction must be being fed from an earlier stuck and

unresolved experience of rejection and humiliation.

Homeopathic treatment can help to heal the pain and undo this past

conditioning so that we are unencumbered by our early negative programing, and

so able to respond in a more wholesome way, leading to healthier relationships,

peace of mind, and a far greater sense of well-being. This is the way to really

heal addiction; to remove the susceptibility towards it, so that it has nothing

to attach to.

In the homeopathic pharmacopeia we have over 3000 remedies of which many

can be used to heal this early emotional patterning. Each homeopathic remedy

has its own unique highly developed ‘picture’. The homeopath’s task is to find

the remedy whose picture most closely resembles the case history of the

patient. When the correct remedy is given, it triggers a healing response in

the person, often revealing and resolving deep emotional issues, as well as

physical ailments and predispositions towards disease.

The first step for the addict though is the realization that they have a

problem and then the willingness to address it. It should now be clear that ‘just

saying no’ is not enough, that detoxing by itself is not enough. Remember that

addiction is about self-medicating for pain, distress, depression… It is these

deeper issues that need to be addressed in order to fully heal.